Revival of the Monroe Doctrine and the Future of the Western Hemisphere

The recent US strike in Venezuela and the reported abduction of President Nicolas Maduro and his wife have triggered serious regional tensions. The Trump administration is prosecuting Maduro and his wife on narcoterrorism charges, a move critics describe as illegal and a violation of international law. At the same time, President Trump has openly stated intentions to control and manage Venezuela’s oil reserves, exposing the political and economic motives behind the operation. Although relations between the two countries had been strained for years, direct military intervention took place within a month of the renewed Monroe Doctrine.

Since the start of his second term, Trump has repeatedly emphasized reasserting US dominance in the Western Hemisphere. This became a central priority in the 2025 US National Security Strategy, which elevates the hemisphere to the top of US strategic concerns. The document adopts a Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which critics have dubbed the Donroe Doctrine. Historically, this approach has been linked to interventionism, support for authoritarian regimes, suppression of leftist movements, and strategic control of natural resources across the Americas. The recent operation in Venezuela is widely viewed as the first concrete expression of this revived doctrine. It signals a more aggressive regional agenda and rising frictions with Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, and even Denmark over Greenland.

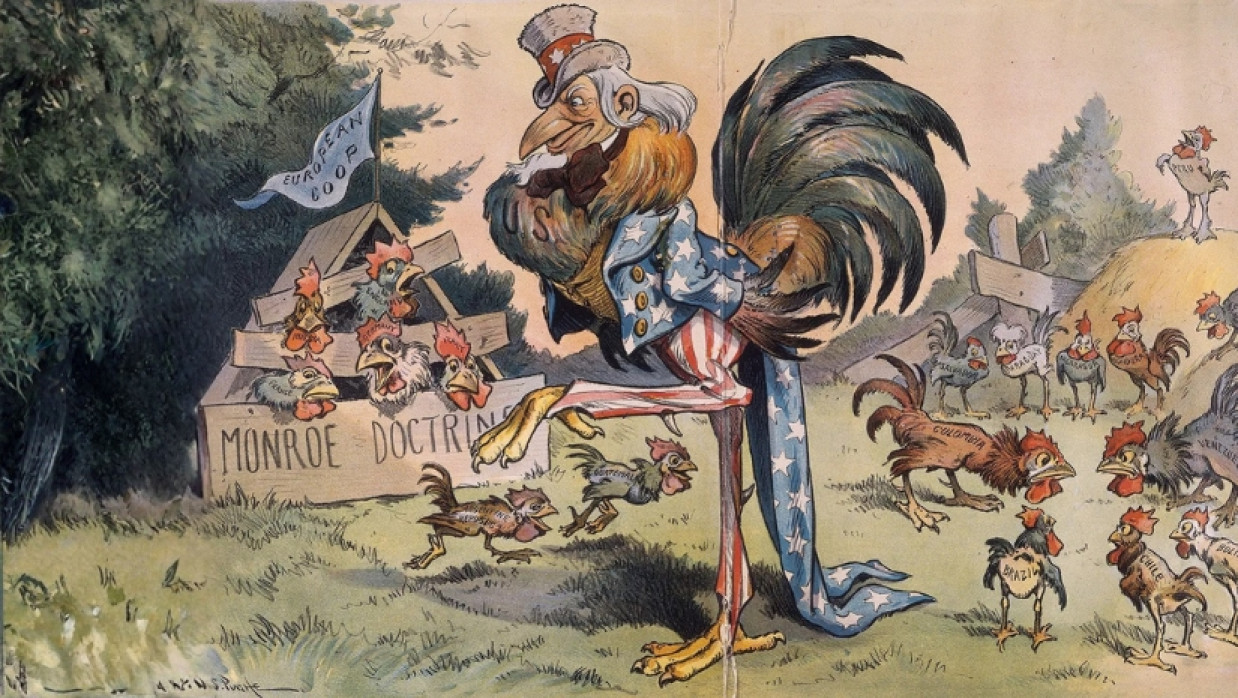

The Monroe Doctrine was declared by President James Monroe in his 1823 annual message to Congress. It framed the Western Hemisphere, including North America, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, as a US strategic security sphere. While security was presented as the primary justification, the underlying aim was to consolidate control over the region’s vast resources. The doctrine began as a warning to Europe against recolonizing newly independent Latin American republics, but it later evolved into a rationale for US intervention. By the early twentieth century, after President Theodore Roosevelt announced the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary, it was used to justify repeated military interventions across the Caribbean and Central America. What began as protection from European empires later became a rationale for building an American one.

During the Cold War, this pattern intensified. Washington backed military juntas, coups, and counterinsurgency efforts against nationalist and leftist movements under the banner of anti‑communism. In Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964, Chile in 1973, and Argentina during the Dirty War, US policy aligned with authoritarian regimes to retain influence over domestic politics and, most importantly, natural resources within the broader logic of Cold War geopolitics. These regimes carried out disappearances, torture, and systematic human rights abuses. Internal left movements were treated as proxies for external communist intrusion. Thousands of lives were lost and democratic trajectories were derailed.

After the Cold War, many assumed the Monroe Doctrine had faded. Yet energy politics, migration pressures, and growing competition with China and Russia brought it back into policy discourse. Trump revived the doctrine as part of a Make America Great Again agenda and reasserted dominance over the hemisphere. The Western Hemisphere has been redefined not simply as a region of interest, but as a region of privileged influence.

Talk of confronting Cuba, intimidating Nicaragua and Colombia, disciplining Mexico over migration and security, and even speculating about Greenland points to a broader shift toward assertiveness. What is unfolding is not merely a return to an old doctrine, but a modernization of imperial influence framed in terms of security, competition, and resource access. Trump’s repeated interest in acquiring Greenland suggests that even long‑standing allies are not immune from pressure under this revived hemispheric agenda.

If this trajectory continues, the Americas may enter a new era of hierarchical regional order where power, not law, defines relations among states. Smaller nations will face increasing coercion, economic leverage, and political interference. Great‑power rivalry with China and Russia will be used to justify deeper militarization and intervention. Countries will hear a familiar message: sovereignty is conditional and Washington defines stability. This risks reinforcing cycles of polarization, anti‑US nationalism, and militarization. Ironically, such policies may create the very insecurity and instability they claim to prevent.

About the Author: Md Ismail Hosain is a student of the Department of Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at ismail769135@gmail.com

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or position of the publisher.