Half the Bangladeshi Students Struggle to Understand What They Read

In classrooms across Bangladesh, millions of children can read but far fewer can understand. Behind the country’s rising literacy rate lies a quieter, more stubborn crisis: a comprehension gap that leaves many students decoding words they cannot grasp.

According to the World Bank’s Learning Poverty Brief (September 2024), more than half of Bangladeshi children aged 10 to 14 about 51 percent cannot read and understand a simple, age-appropriate passage. This measure, known as “learning poverty,” places Bangladesh ahead of its South Asian neighbors but still reveals a deep challenge in foundational education.

Despite impressive strides in school enrollment and gender parity, the ability to truly comprehend written text remains elusive for millions. As the country eyes its 2041 vision of becoming an advanced economy, the question is no longer whether students are in school but whether they are actually learning.

A Paradox of Progress

Bangladesh’s literacy story is, on paper, one of remarkable progress. The adult literacy rate rose to nearly 79 percent in 2024, up from 47 percent in the late 1990s, according to UNESCO. The youth literacy rate among people aged 15 to 24 now hovers around 93 percent, nearly closing the gender gap that once divided boys and girls in education.

Yet this success masks another reality. The latest National Student Assessment (NSA) conducted in 2022 revealed that more than 50 percent of grade 3 and grade 5 students performed below grade level in Bangla reading comprehension. Many could read aloud fluently but struggled to explain what the text meant.

“Reading comprehension is not just about decoding letters,” says education researcher Dr. Shafiq Rahman, who contributed to the NSA analysis. “It’s about connecting ideas, inferring meaning, and applying knowledge. That’s where we are falling short.”

Learning Poverty: Beyond School Attendance

The concept of “learning poverty,” introduced jointly by the World Bank and UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics, measures the share of 10-year-olds who cannot read and understand a short, age-appropriate story. It combines two deprivations: the learning deprivation (children in school who still cannot read proficiently) and the schooling deprivation (children of primary school age who are out of school altogether).

By this measure, Bangladesh’s 51 percent learning poverty rate is lower than South Asia’s average of 59 percent and significantly better than Pakistan’s 60 percent or India’s 56 percent. It is also lower than the 61 percent average across lower-middle-income countries.

But the progress comes with caveats. While only 2 percent of Bangladeshi children are out of school a commendable rate the remaining 50 percent of those enrolled still fail to reach the minimum proficiency benchmark by the end of primary school. The problem, experts warn, is not access but quality.

What the Data Show

The 2022 NSA, the most recent nationwide learning assessment, paints a nuanced picture. Conducted by the Directorate of Primary Education, it tested more than 30,000 students across grades 3 and 5.

Over half of students scored below grade-level expectations in Bangla reading comprehension. Students performed better in literal recall remembering facts from a passage than in inferential or analytical questions, where they needed to interpret or reason.

There were no significant gender differences, but urban-rural disparities were stark. English reading comprehension was notably weaker, with more than 50 percent unable to understand simple sentences.

Regional inequalities also persist. Students in Dhaka and Chattogram districts scored substantially higher than those in Sylhet, Rangpur, or the Chittagong Hill Tracts, where Bangla is often a second language. In remote areas like Bandarban, literacy rates among adults still linger around 54 percent, nearly 25 points below the national average.

Teachers, Training, and Textbooks

Education officials acknowledge that comprehension requires more than textbooks and exams it demands trained teachers who can nurture critical thinking. Yet Bangladesh faces a shortage of qualified primary teachers, especially in rural areas.

A 2024 report by the Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE) found that one in five government primary schools lacks a full complement of trained teachers, and many teachers handle multi-grade classrooms with limited resources.

The curriculum, revised in 2023 to emphasize “competency-based learning,” aims to shift focus from rote memorization to understanding. But implementation remains uneven.

“Students are memorizing stories without discussing them,” says Nasima Akter, a primary school teacher in Barisal. “They can recite entire paragraphs but cannot explain a single sentence.”

COVID-19 and the Lost Years

The COVID-19 pandemic deepened an already fragile situation. School closures that lasted over 18 months among the world’s longest caused widespread learning loss.

UNICEF estimates that students in Bangladesh lost nearly a full year of effective learning during the pandemic. Remote learning through television and online platforms reached only a fraction of students; less than half had consistent access to the necessary devices or connectivity.

Even after schools reopened in 2022, recovery was uneven. “Children returned to classrooms, but many had forgotten how to read fluently,” says Dr. Rahman. “We are still catching up.”

Global Context: A Shared Struggle

Bangladesh’s struggle mirrors a broader global crisis. The World Bank estimates that 70 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10, up from 57 percent before the pandemic.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the figure reaches 89 percent; in Latin America and the Caribbean, 79 percent. Even in middle-income regions like the Middle East and North Africa, learning poverty rose from 63 to 70 percent post-pandemic.

Globally, the economic cost of this learning crisis is staggering an estimated $11 trillion in lost lifetime earnings for the current generation of students, according to World Bank simulations.

High-income countries remain exceptions. Finland, Singapore, and South Korea report near-universal reading proficiency among children, with learning poverty below 10 percent. But in most of the world, the challenge is both educational and economic.

Inside the Numbers: Adults and Adolescents

While child learning is the focus of global tracking, adult literacy remains a crucial marker of long-term progress. Bangladesh’s 25 million illiterate adults mostly in rural areas and among older women represent one of the largest adult literacy gaps in the world.

The government’s National Literacy Campaign, restarted in 2023, aims to eliminate adult illiteracy by 2030. Yet funding constraints remain severe. Bangladesh spends the equivalent of $223 per primary school child (PPP-adjusted) roughly 81 percent below the South Asian average.

“Spending more efficiently is as important as spending more,” notes Md. Shahidul Islam, an education economist with the World Bank’s Dhaka office. “We need to focus resources where learning outcomes are weakest.”

Gender and Equity: A Narrowed but Persistent Divide

Bangladesh has long been celebrated for achieving gender parity in primary and secondary enrollment, a rare accomplishment in South Asia. Girls now slightly outperform boys in most literacy measures.

But gender gaps resurface in higher education and employment, where literacy and comprehension are crucial for advancement. Moreover, boys exhibit slightly higher learning poverty (54 percent) than girls (49 percent), largely due to higher dropout rates among adolescent males in rural areas.

“In rural communities, boys often leave school early to work,” says Farhana Yasmin, an NGO education coordinator in Mymensingh. “Girls stay enrolled, but their reading materials rarely encourage analytical thinking. Both groups are underserved.”

Reforms on the Horizon

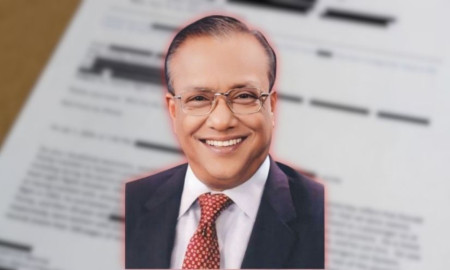

Bangladesh’s education authorities are signaling a renewed focus on improving learning outcomes, particularly reading comprehension. Chowdhury Rafiqul Abrar was appointed Adviser for Education on March 5, 2025, and in public remarks has emphasized the need to enhance the quality of education and incorporate modern, technology-supported methods.

The Directorate of Primary Education has indicated that a new framework for the National Student Assessment (NSA) is under development, aimed at better measuring comprehension rather than rote reading. While no official testing dates or pilot schedules have been publicly released, the review suggests an eventual rollout could occur in the next few years.

Officials are also reviewing international assessment programs such as PIRLS and PISA, which could allow Bangladesh to benchmark its reading outcomes against other countries. Education experts note that any meaningful improvement will depend not only on new assessments, but also on equipping teachers with practical training and resources to foster comprehension-focused instruction across classrooms nationwide.

The Stakes of Understanding

The implications of poor comprehension stretch far beyond the classroom. Students who struggle to understand written text often fall behind in every subject science, math, history and are less likely to complete secondary school.

At a macro level, weak literacy undermines economic productivity. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index estimates that children in Bangladesh will achieve only 46 percent of their potential productivity as future workers if education quality does not improve.

A Race Against Time

Bangladesh’s literacy drive is one of its greatest success stories but comprehension is the next frontier. Achieving the government’s target of 100 percent literacy by 2030 will mean little if half of those who can read still fail to understand.

Lessons from countries like Vietnam and Kenya suggest that meaningful improvements in reading comprehension require intensive teacher training, community involvement, and early assessment reforms. Bangladeshi policymakers have indicated that they are studying these models to inform potential reforms.

Consider a fifth-grade student in Gazipur. The student can read a story about the Padma Bridge but struggles to explain its purpose. When prompted by the teacher, the student slowly begins to articulate: “It connects people… it connects the country.”

This example illustrates the central challenge facing Bangladesh: literacy alone is not enough. Reading comprehension connects words to meaning, lessons to understanding, and education to opportunity. Without it, gains in enrollment and literacy risk remaining hollow victories.

In many ways, reading comprehension does the same it connects words to meaning, and education to opportunity. Without it, literacy remains a hollow victory.

By the Numbers (2025)

|

Indicator |

Bangladesh |

South Asia Average |

Global Average |

|

Adult Literacy Rate (15+) |

79% |

77% |

88% |

|

Youth Literacy Rate (15–24) |

93% |

91% |

93% |

|

Learning Poverty (Age 10–14) |

51% |

59% |

70% (LMICs) |

|

Learning Deprivation |

50% |

55% |

58% |

|

Schooling Deprivation |

2% |

8% |

8% |

|

Adult Illiterates |

25 million |

— |

739 million (worldwide) |

|

Primary Education Spending per Child |

$223 (PPP) |

$1,180 (regional avg) |

$11,300 (OECD avg) |

Sources: World Bank Learning Poverty Brief (Sept 2024); UNESCO International Literacy Factsheet (2025); National Student Assessment (2022); CAMPE Education Report (2024).

Expert Opinion

Dr. S M Hafizur Rahman, Professor at the Institute of Education and Research, said problems with reading comprehension are not limited to the early grades. In our academic setup, the reading taught in Class 5 is essentially the same as in Class 8—there is no significant conceptual difference. Even after repeated teaching, many students still fail to gain clarity. He further added that when the conceptual demands of reading become even more complex, there is no opportunity to reduce reading poverty; instead, it may increase further. The purpose of the content taught to children is to create alignment between their reading and their environment. But when we teach them, we fail to connect the material to their world. As a result, reading gradually becomes incomprehensible to them.

As we progress to higher grades, the connection between content and context drifts further apart. Consequently, the link between reading and comprehension weakens. Since we have less problem-based or context-based learning, students are unable to clarify their concepts. Even when these students advance to higher education, this conceptual inferiority persists. To improve, we must develop our curriculum, making the existing one a top priority.

Bangladesh’s challenge is not whether its children can read, but whether they can comprehend. As global attention shifts from schooling access to learning outcomes, comprehension stands as the truest test of educational progress.

Half a century after independence, the nation has taught nearly every child to read. The task now is to help them understand.