Broken Trust, Failing Banks: The Deepening Financial Crisis in Bangladesh

Walk into any middle-class home in Dhaka today and you'll hear the same anxious question over evening tea: "Is our money safe in the bank?" A decade ago, this would have seemed absurd. Today, it reflects a harsh reality—Bangladesh's banking sector is in crisis, and ordinary depositors are beginning to feel the tremors.

The crisis rests on three pillars of failure: soaring non-performing loans, collapsing asset quality, and dangerously low capital adequacy. Together, they've created a perfect storm threatening the entire financial system.

The NPL Explosion: Asia's Worst Numbers

Non-performing loans—money lent but not repaid—have reached catastrophic levels. As of March 2025, NPLs stand at Tk 420,335 crore, representing 24.13 percent of all loans. Total distressed assets have ballooned to Tk 756,526 crore—nearly 45 percent of all lending, comprising Tk 3.46 trillion in NPLs, Tk 3.48 trillion in rescheduled loans, and Tk 623 billion in written-off loans.

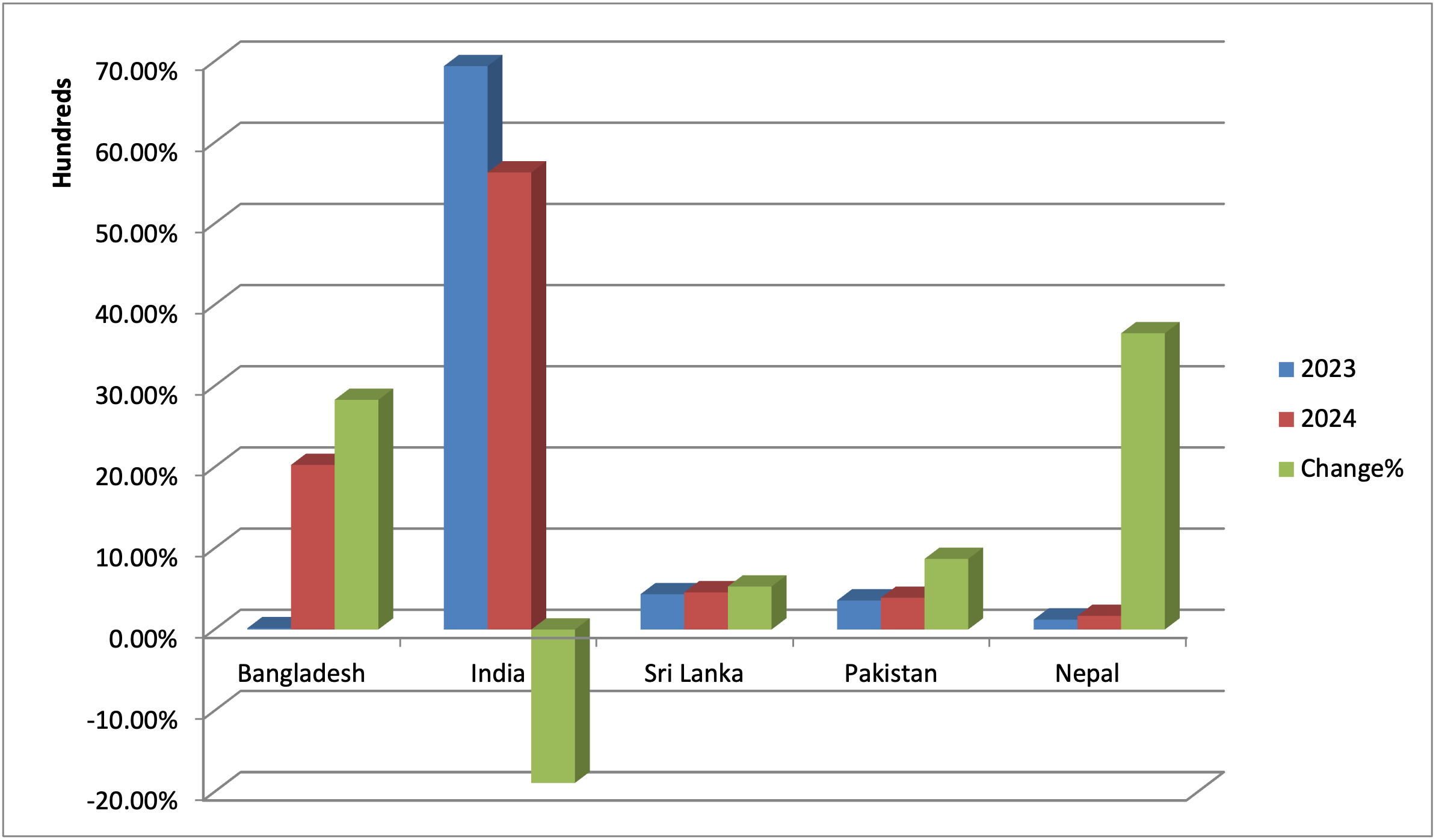

NPL Ratios of South Asian Countries

|

Country |

2023 |

2024 |

Change% |

|

Bangladesh |

15.80% |

20.27 |

28.3 |

|

India |

69.41 |

56.31 |

-18.9 |

|

Sri Lanka |

4.35 |

4.58 |

5.3 |

|

Pakistan |

3.58 |

3.9 |

8.7 |

|

Nepal |

1.23 |

1.68 |

36.5 |

Source: Asian Development Bank

According to the Asian Development Bank's latest report, Bangladesh now has the highest NPL ratio in all of Asia at 20.27 percent. The ADB's assessment is blunt: Bangladesh's banking sector is "the region's most structurally vulnerable." Our NPL ratio jumped 11.2 percentage points in just one year—a spike the ADB calls unprecedented.

Behind these numbers are real stories: small businesses unable to expand, young entrepreneurs turned away from loan windows, families watching their savings institutions teeter. Alarmingly, 71 percent of these bad loans are concentrated in just 10 banks—this isn't a system-wide problem but a targeted failure where governance collapsed.

While our South Asian neighbors have been cleaning up their act—India slashed its NPL ratio from 3.4 percent to 2.5 percent, Pakistan reduced to 3.9 percent, and Sri Lanka maintained 4.58 percent—we've moved in the opposite direction. Our neighbors faced the same global challenges. The difference? Their banks had stronger foundations, better governance, and regulators with real teeth.

Asset Quality Collapse: Banks Running Out of Money

Asset quality measures how healthy a bank's loan portfolio is—essentially, how likely borrowers are to repay. When asset quality deteriorates, banks lose their ability to generate income and meet obligations. Bangladesh's asset quality has degraded so severely that many institutions can no longer function as viable financial intermediaries.

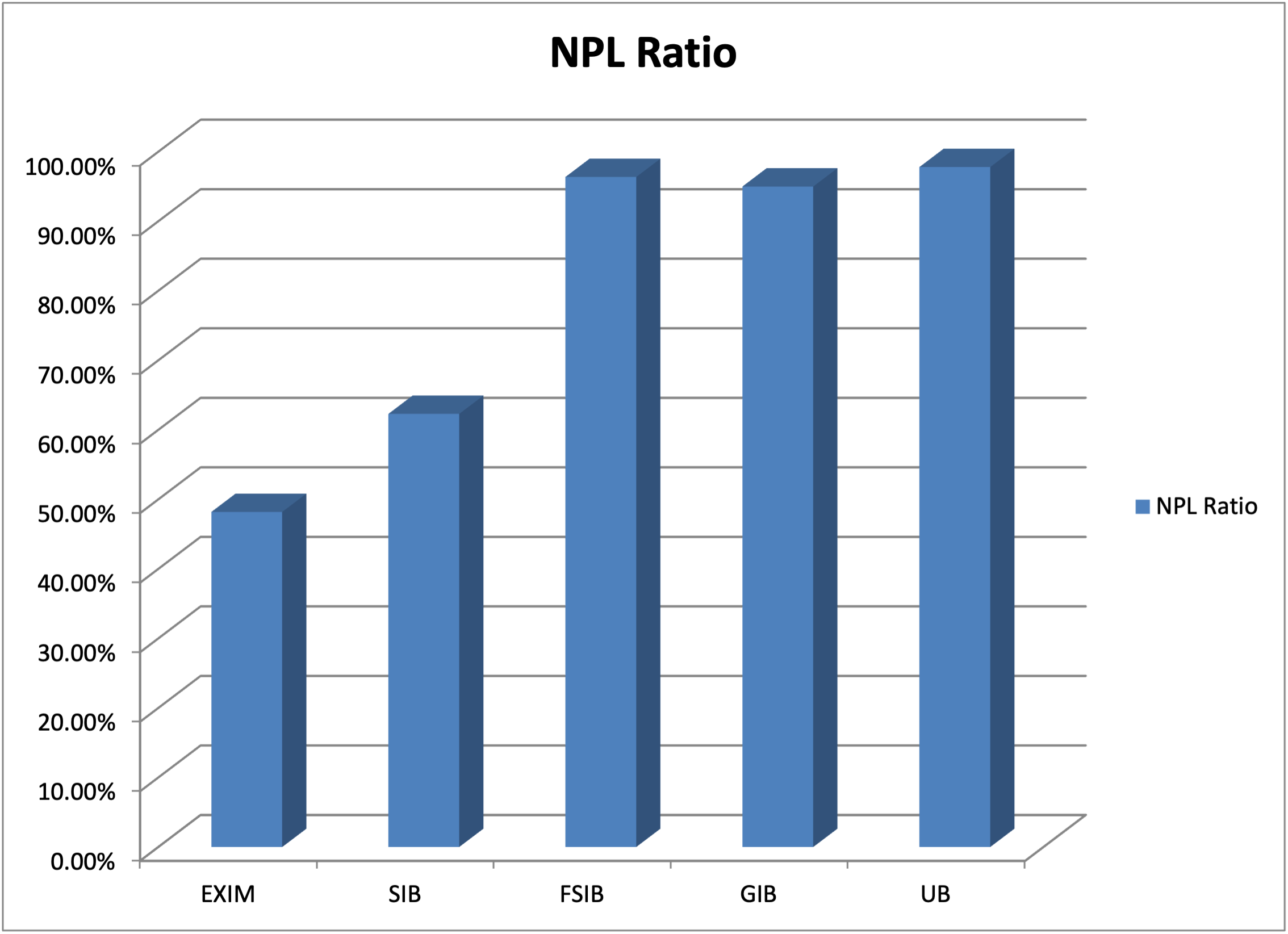

NPL Ratios of five troubled Islamic banks:

|

BANK |

NPL Ratio |

|

EXIM |

48.20% |

|

SIB |

62.30% |

|

FSIB |

96.37% |

|

GIB |

95% |

|

UB |

97.80% |

Independent audits by KPMG and Ernst & Young (EY) revealed nightmare scenarios in five troubled Islamic banks: EXIM Bank has 48.2 percent NPLs, Social Islami Bank 62.3 percent, while First Security Islami Bank (96.37 percent), Global Islami Bank (95 percent), and Union Bank (97.8 percent) are essentially non-functional.

Poor asset quality doesn't just hurt individual banks—it triggers a credit crunch across the economy. Small and medium enterprises, the backbone of employment in Bangladesh, face severe difficulty accessing loans. A garment factory owner in Narayanganj can't get working capital for export orders.

Capital Adequacy Crisis: No Cushion Left

Capital adequacy measures a bank's ability to absorb losses and continue operating during downturns. Under Basel III international standards, banks must maintain a Capital-to-Risk Weighted Assets Ratio of at least 12.5 percent.

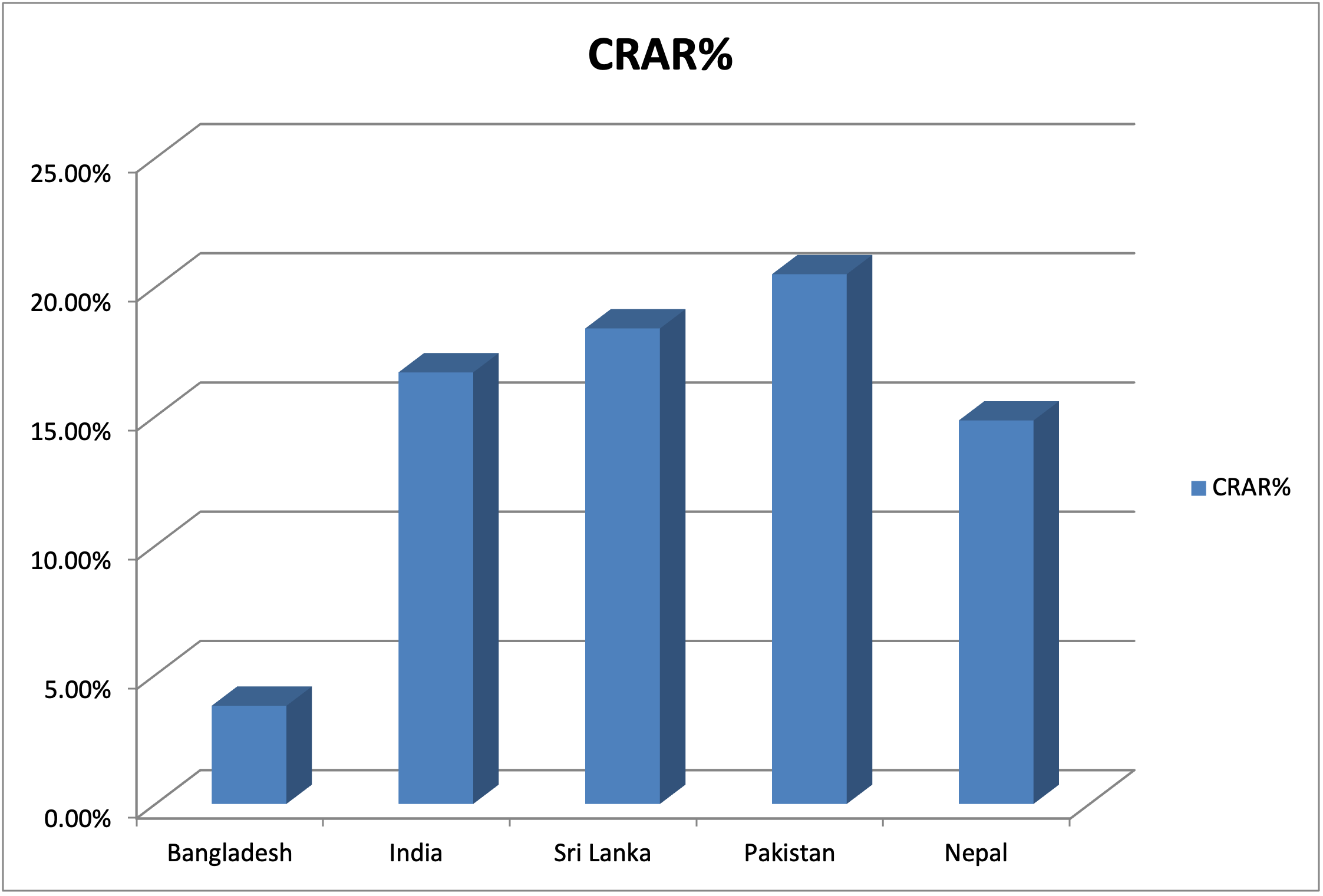

CRAR value of South Asian Countries

|

Country |

CRAR% |

|

Bangladesh |

3.80% |

|

India |

16.70% |

|

Sri Lanka |

18.40% |

|

Pakistan |

20.50% |

|

Nepal |

14.84% |

Bangladesh's average CRAR has collapsed to just 3.80 percent—the lowest in South Asia and far below the minimum requirement. Pakistan's banks maintain 20.50 percent, Sri Lanka's 18.4 percent, and India's 16.70 percent. We're not even close.

Twenty of our banks collectively need Tk 171,789 crore just to meet minimum capital standards. That's not money for growth or expansion—that's money just to stay alive. Without adequate capital, banks can't absorb the losses from their mounting NPLs. They can't lend to creditworthy borrowers. They can't protect depositors. They're effectively operating on borrowed time.

The provisioning gap compounds the capital crisis. Banks must set aside provisions from profits to cover bad loans. As of June 2025, 18 banks failed to meet provisioning requirements. The shortfall exploded from Tk 26,585 crore in March 2024 to Tk 170,655 crore in March 2025—a six-fold increase in just one year. Bangladesh Bank barred these institutions from paying dividends, but the damage is done.

Years of Mismanagement

This three-pronged crisis didn't materialize overnight. It's been brewing for years, fed by political interference, weak governance, and corruption. Too many loans went to well-connected borrowers with little scrutiny. Too many bank boards were filled through patronage rather than competence. When loans went bad, they were simply rescheduled, kicking the can down the road and masking the true extent of NPLs.

Bangladesh Bank, our central regulator, has seen its authority eroded by political pressure. When regulators can't regulate independently, the system becomes a playground for the well-connected and a minefield for ordinary depositors. In a system where banks dominate 86 percent of financial intermediation, these failures have economy-wide consequences.

Can Merging Banks Work?

Facing operational paralysis, Bangladesh Bank floated a controversial merger plan to consolidate the five troubled Islamic banks into a single state-owned entity. However, the KPMG and Ernst & Young audits reveal this plan is unviable. Merging all five banks would create a massive institution where 75-80 percent of assets are non-performing—essentially a zombie bank requiring endless government subsidies.

A more realistic approach: selectively merge only EXIM and SIB, which have some chance of recovery. FSIB, GIB, and UB should be liquidated in an orderly manner with priority given to protecting individual depositors through the deposit insurance system.

The Way Forward

The path isn't mysterious. We need comprehensive reforms targeting all three crisis factors simultaneously.

For NPLs: Fast-track loan recovery tribunals, tougher bankruptcy laws, and public disclosure of defaulters. Stop the practice of endless rescheduling that hides bad loans. Strengthen the Credit Information Bureau to prevent serial defaulters from accessing new credit.

For asset quality: Implement rigorous credit risk assessment before loan approval using modern AI-driven models. Diversify portfolios away from large, concentrated exposures. Establish early warning systems to catch problems before they metastasize.

For capital adequacy: Recapitalize viable banks—but only with ironclad governance reforms attached. Wind down institutions beyond saving in an orderly manner that protects depositors. Enforce Basel III compliance rigorously with no exceptions.

Above all: Depoliticize bank boards and install competent professionals based on merit. Link compensation to performance—bankers should retain at least 50 percent of their deposits in their own institutions to share in the risk. Give Bangladesh Bank true independence to supervise without political interference. Hold directors and executives legally accountable for fraud and gross negligence.

The Choice Before Us

Bangladesh stands at a crossroads. We can continue applying band-aids and watch our banking sector implode. Or we can convene the political courage to implement real reforms.

Every day without decisive action, NPLs grow, asset quality deteriorates further, and capital erodes. We've seen what happens when banking crises spin out of control. We also know that recovery is possible—India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka are proving it.

The banking sector is the circulatory system of our economy. When it fails, we all fail. Right now, it's failing. The question is: what are we going to do about it?

Dr. FARHANA YASMIN LIZA

Associate Professor

Department of Business Administration

Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the newspaper or its editorial board.