Bangladesh at the Bottom Globally in Primary and Secondary Education Spending

The government spends only Tk 27,206 per student annually

- ২৫ অক্টোবর ২০২৫, ১৫:৩১

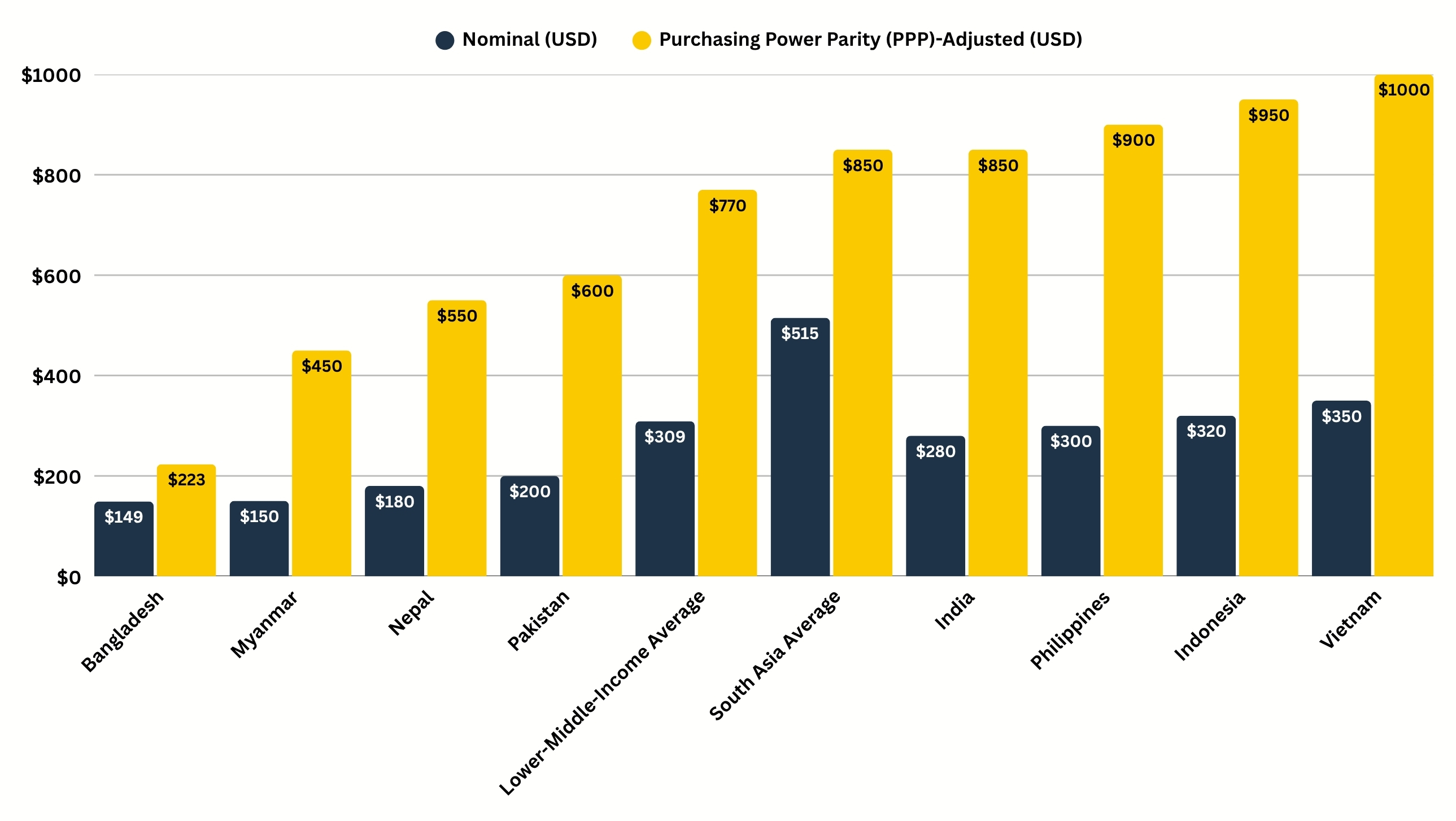

Every child in Bangladesh now goes to school—a proud milestone on paper! Yet, in 2025-26, the government plans to spend just Tk 27,206 ($223, adjusted for purchasing power parity) per student, one of the lowest amounts globally. India invests nearly three times more and Vietnam over four times more per student, leaving Bangladesh’s classrooms overcrowded, teachers underpaid, and learning materials scarce.

With just 1.5 percent of GDP going to education, the question remains: are we investing enough in our children’s future?

The government has proposed Tk 95,644 crore for education in 2025–26, covering primary, secondary, technical, and madrasa institutions. However, the per-student allocation remains too low to ensure quality learning.

Education makes up 12.1 percent of the total budget and only 1.53 percent of GDP. Experts recommend allocating 4 to 6 percent of GDP or 15 to 20 percent of public funds. Bangladesh still falls far short of that standard, leaving schools underfunded and the nation’s progress at risk.

Professor Dr. Mohammod Moninoor Roshid of the Institute of Education and Research (IER), University of Dhaka, told The Daily Campus that building a strong foundation from the primary level is crucial. He said the recent report by The Daily Campus highlighting Bangladeshi students’ lack of reading comprehension reflects a deeper issue — how the government and the nation prioritize education. “Governments come and go, but no one is truly willing to take responsibility,” he remarked, adding that the education budget has been shrinking year after year.

Per-Student Spending

Spending per student highlights the issue. A 2024 report shows primary education spending fell from Tk 19,642 ($161) in 2021 to Tk 18,178 ($149) in 2022. This is a basic dollar amount.

Adjusted for what money buys in Bangladesh, it is Tk 27,206 ($223) per primary student, per a 2024 World Bank report. From 2016 to 2022, the average was Tk 16,592 ($136). Bangladesh ranks very low globally.

“Globally, there is a clear benchmark for how much of a country’s GDP should go to education,” said Professor Dr. Mohammod Moninoor Roshid. “In Bangladesh, the number of schools and teachers has grown, but the share of education expenditure has steadily declined. The government highlights an increasing budget every year, but in reality, it hasn’t kept pace with the system’s growth. Unlike UNESCO’s standard or countries like Vietnam, we have consistently underinvested—because education has never truly been a national priority.”

Data across all school levels is not always complete. But the trend is clear. Bangladesh spends less per child than many similar nations. This limits what schools can provide.

Comparisons with Other Countries

According to international data, lower-middle-income countries like Bangladesh spent an average of about Tk 37,698 ($309) per child on education in 2022. Bangladesh, however, spent only Tk 18,178 ($149) per child at the primary level. That is less than half the average, and the gap is striking.

In contrast, Vietnam, which is often praised for strong student performance, spends about Tk 42,700 ($350) per primary student in nominal terms, or Tk 122,000 ($1,000) when adjusted for purchasing power parity, which means after accounting for price differences between countries. This higher level of investment has helped Vietnam achieve much better learning outcomes.

Other Southeast Asian countries show similar trends. Indonesia spends about Tk 39,040 ($320) nominally, or Tk 115,900 ($950) in PPP terms. The Philippines spends around Tk 36,600 ($300) nominally, or Tk 109,800 ($900) PPP. Each of these countries invests significantly more in each child’s education than Bangladesh.

Even within South Asia, Bangladesh lags behind. Across the region, government spending per school-age child increased from Tk 26,596 ($218) in 2010 to Tk 62,830 ($515) in 2022. Bangladesh remains below that average and needs to catch up to its neighbors.

India spends around Tk 34,160 ($280) per primary student, or Tk 103,700 ($850) PPP. Pakistan spends roughly Tk 24,400 ($200) nominally, or Tk 73,200 ($600) PPP. Nepal and Myanmar spend less than both, with Tk 21,960 ($180) and Tk 18,300 ($150) nominally, or Tk 67,100 ($550) and Tk 54,900 ($450) PPP.

Rich countries spend much more. OECD nations average Tk 1,464,000 ($12,000) per primary student. This includes small classes, tech, and extra support. Bangladesh cannot match this yet.

Norway spends Tk 2,168,638 ($17,779) per primary student. The USA is at Tk 1,891,000 ($15,500) for elementary and secondary. The UK is around Tk 1,464,000 ($12,000). These cover advanced tools and counseling.

In 2023, Bangladesh used 10.67 percent of its budget on education. The world average is 13.9 percent. This shows education gets less focus here.

Family Costs and Inequity

Families face extra costs due to low public funds. They pay for uniforms, tuition, and travel. A 2023 study says families spend Tk 13,882 ($114) per primary student.

These costs create unfair gaps. Families who can afford extras like tuition see better results. Poor children fall behind. This splits rich and poor learners.

Dr. Roshid said low budget allocations have left teachers underpaid and more focused on private tutoring than classroom teaching. As government spending falls, parents are paying more out of pocket, moving children to private or foreign schools. “This has created a brain drain as our best talents are leaving while education quality at home keeps declining,” he said.

If this goes on, Bangladesh risks losing potential. Its large young population could drive growth. But weak skills hurt jobs and the economy. Better learning is vital.

Expert Insights

Dr. Roshid said that the lack of political will stems from a lack of personal stake in public education.

“Political leaders’ own children study in private or foreign institutions, so they feel no ownership of the national system,” he said. “When those in power are not stakeholders, they don’t invest in improving it. This detachment has weakened education quality and skills development, leading to growing frustration and loss of public confidence in the system.”

Education expert Ahmed Shahriar highlights budgeting issues. He says noting low funds is not enough. Spending must be smarter.

Shahriar questions the focus on buildings. Model schools do not solve everything. Classroom conditions matter more.

One teacher cannot handle 80 to 100 students well. It is too much for one person. More teachers are needed for better learning.

Extra training alone does not fix crowded classes. Controlled classrooms help children learn. Chaos holds them back.

Professor Dr. Monira Jahan of the Institute of Education and Research at Jagannath University told The Daily Campus that Bangladesh’s spending on primary and secondary education is extremely low compared to global standards, which is having a profound impact on the quality of its education system. “This is truly a matter of serious concern,” she said.

She explained that the huge gap in education expenditure clearly shows that students in Bangladesh are being deprived of access to quality learning. Due to the limited budget, schools cannot provide adequate classrooms, learning materials, technology, or library facilities. With such insufficient funding, it is also not possible to invest properly in infrastructure development, teacher training, or improving teaching quality.

“To produce quality teachers, proper training and fair salaries are essential. Similarly, addressing students’ learning gaps requires special programs—and that demands sufficient budget,” she said. “Classrooms in Bangladesh are often overcrowded, with 60 to 70 students in each. Because of funding shortages, it becomes difficult to teach effectively, support teachers adequately, or run remedial programs for weaker students.”

As a result, many children are falling behind in acquiring basic reading, writing, and comprehension skills at the primary level. Several international assessments have shown that a majority of Bangladeshi primary students fail to achieve the grade-level literacy and learning standards expected of them.

Policy Solutions

- Increase education’s share of GDP. The current 1.53 percent is too low. Aim for 4 to 6 percent for real learning gains.

- Spend money wisely. Focus on early reading and math. Train teachers, provide books, help slow learners, and improve schools in poor areas.

- Track spending per child. Check if it grows, especially for needy students. This helps make education fairer for all.

- Use private partnerships carefully. Team-ups with private groups or donors can add resources. But they must focus on fairness and quality, not just more schools.

- Cut costs for families. Uniforms, books, and tuition block many poor children. Supporting these costs makes education equal for all.

Bangladesh has nearly achieved universal primary education, but learning remains the real challenge. Each student receives too few resources for quality education, leaving many without basic skills. Without stronger and smarter investment, access alone will not secure the country’s future.