Politics vs Pedagogy: Why Tarique Rahman’s academic journey remained "incomplete"

- ১৫ জানুয়ারি ২০২৬, ১৪:৩৯

The academic background of Tarique Rahman, chairman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), has long been a subject of public discourse. Much of the criticism directed at the political leader centers on his inability to complete his formal higher education. For the son of late President Ziaur Rahman and three-time Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, the question of why he could not finish his university degree has frequently surfaced in political rhetoric, talk shows, and social media debates.

However, a closer look at history suggests that this interruption was less a matter of personal failure and more a consequence of the prevailing political instability, the anti-autocracy movement, and state-sponsored repression of the time.

A Childhood Shaped by Detention

According to his secondary school records, Tarique Rahman was only three years old during the Liberation War of 1971. At that tender age, he was detained along with his mother, Begum Khaleda Zia, and younger brother, Arafat Rahman Koko, as part of the crackdown on the families of freedom-fighter military officers. Losing his father at a young age and experiencing early state-enforced confinement set a precedent for a life lived under extraordinary pressure.

By 1986, during the lead-up to the controversial elections under the Ershad regime, Tarique Rahman made a public appearance at the National Press Club to denounce the security agencies' attempts to stifle the opposition movement. Consequently, the military government under General Ershad repeatedly placed him and his mother under house arrest to silence their voices.

The Dhaka University Years

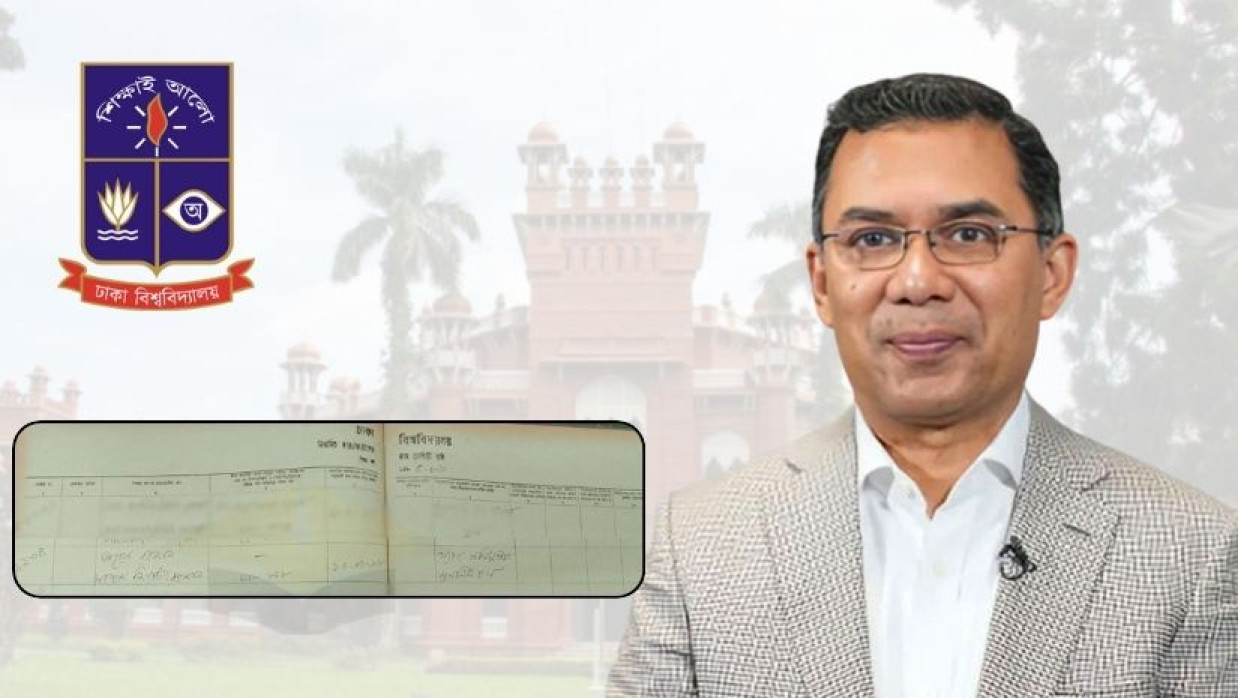

After completing his Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) from BAF Shaheen College, Dhaka, Tarique Rahman enrolled in the Department of Law at Dhaka University for the 1985-86 academic session. He later transferred to the Department of International Relations, and as a student, Tarique was allotted a seat at Sir Salimullah Muslim (SM) Hall.

.jpg)

During this period, the campus environment was marred by the autocratic rule of Ershad. Political persecution, mass protests, and severe "session jams" (academic delays) crippled the university's functional capacity.

Mamunur Rashid, an office assistant at Kabi Jasimuddin Hall and a witness to the era, recalled the volatility. "During the 90s, classes were almost non-existent due to the anti-Ershad movement. The campus was a battleground of gunfire. People were killed; once, even a stray cow was shot dead in the crossfire," he told The Daily Campus. He noted that the politics of "hall occupation" meant that exams scheduled for 1977 were often held as late as 1981.

Expert Perspectives: Politics vs. Pedagogy

Professor Mohammad Ainul Islam of the Political Science Department at DU noted that Tarique Rahman’s situation was not unique. "The political climate from 1971 through the 1980s was so turbulent that many from political families found it impossible to complete formal degrees. Being a member of the Zia family made him a primary target of the state’s administrative hurdles," he said.

Professor Islam further contextualized the issue globally: "Formal degrees are not a prerequisite for political leadership. Neither Abraham Lincoln nor George Washington held traditional college degrees. Tarique Rahman’s education was forged through real-world political challenges and family responsibilities, which often carry more weight in leadership than a parchment."

Dr. Himadri Shekhar Chakraborty, the current Acting Controller of Examinations at DU and a contemporary of Tarique Rahman, echoed these sentiments regarding the atmosphere of the mid-80s. "While the quality of students was high, the environment was not conducive to study. Hall-centric clashes and gunfire were frequent. General students, through no fault of their own, were the primary victims of this instability," he said.

Security Concerns and State Pressure

Professor Dr. Nurul Amin Bepari, former Chairman of the Political Science Department and a direct teacher of Tarique Rahman, described the era as one of "total turmoil."

"As the son of Ziaur Rahman, it was incredibly risky for Tarique to attend classes publicly. His security was under constant threat," Dr. Bepari explained. "The prevalence of weapons on campus and the constant threat of violence made regular attendance nearly impossible for someone in his position."

Ultimately, the combination of active participation in the anti-autocracy movement—having joined the BNP formally in 1988 via the Gabtoli Upazila unit—and the systematic disruption of the national education system by the then-regime, brought a premature end to his formal academic journey at Dhaka University.